June 5, 2025

By: Ferran Garcés

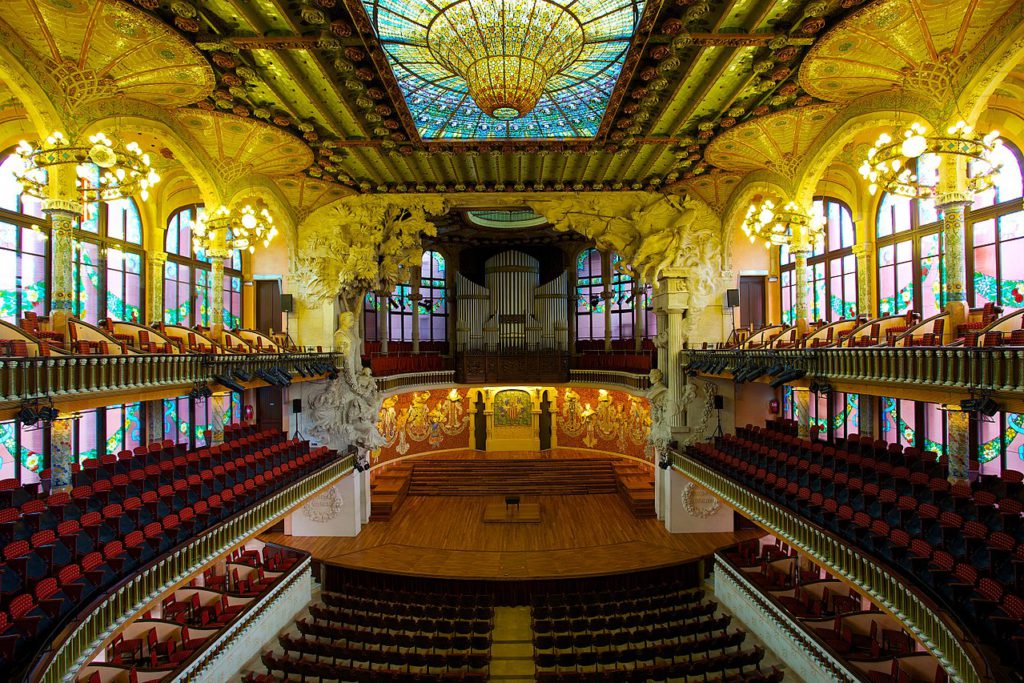

The term modernist, when applied to music, is surrounded by ambiguity (1). Some musicologists even question whether modernist music truly existed, or whether it would be more appropriate to speak of music in the modernist era. In our previous article, we promised to answer this question—or at least try.In search of an answer, we invite you to visit the Palau de la Música Catalana, built by Lluís Domènech i Montaner between 1905 and 1908—at the same time Gaudí was completing Torre Bellesguard. Three sculptural groups in this iconic building summarize the musical ideals of that era. The actual musical landscape, however, was much more complex and would require a much longer text (2).

Let’s begin with the sculptures that dominate the Palau’s stage. The one on the right looks toward Northern Europe and symbolizes “cultured” music. The one on the left looks toward our homeland and represents “popular” music. Music during the modernist period fluctuated between these two currents.

Looking Toward Northern Europe

At one end of the Palau’s stage, galloping horses emerge—sculpted by Dídac Massana and Pau Gargallo. This is a reference to The Ride of the Valkyries, a well-known piece by Richard Wagner, the Romantic composer who dominated Barcelona’s cultural scene from the late 19th to early 20th century, overshadowing the earlier Italian operatic tradition. His influence was so great that in 1901, the Wagnerian Association was founded. As musicologist Roger Alier notes, “just look at the list of members and supporters to find the cream of the Catalan liberal bourgeoisie (3).” Can we hear echoes of this ride in Torre Bellesguard?

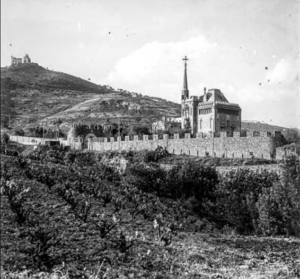

According to Josep M. Vall i Comaposada, a Bellesguard specialist, “It’s possible that when Gaudí was building Bellesguard, he was influenced by the Wagnerian wave that permeated Barcelona’s cultural elites. The image of a mysterious sacred mountain and the fact that King Martin possessed the relic of the supposed Holy Grail would link Bellesguard to the Wagnerian myth of Montsalvat,” the mythical home of the sacred relic in Wagner’s operas Lohengrin and Parsifal (4).

Beneath the ride, the bust of Beethoven stands out—another German composer, representing a country that became a social and cultural model for the modernists (5). It was more than just musical taste; it was also about achieving the level of musical excellence required to perform these composers’ works. In the words of modernism expert Xosé Aviñoa, Catalonia’s theatrical renewal was rooted in Wagner, and its symphonic renewal in Beethoven (6).

The northern inclination grew with interest in the Franco-Belgian school, led by César Franck and Vincent d’Indy. Their introduction to Barcelona came through Catalan composer Enric Morera, who studied in Brussels, and Belgian violinist Mathieu Crickboom, who lived in Barcelona for several years and significantly influenced chamber music development. Another key figure in Catalonia’s musical renaissance was Antoni Nicolau, conductor of memorable concerts featuring both European and local composers, and a leader in music education reform at the Municipal School of Music (7).

Looking Toward Our Homeland…

The second sculptural group is a tribute to Josep Anselm Clavé. A worthy son of the Renaixença, this composer combined artistic talent with social activism and even politics. The choirs bearing his name were primarily made up of workers from all walks of life. Often, instead of performing in theaters, Clavé’s choirs sang in streets and squares, becoming the centerpiece of massive gatherings. At the Palau, Clavé’s bust is accompanied by an allegory of Les flors de maig (1853), his most famous song. The sculptor was again Pau Gargallo.

To understand Clavé’s importance, one must remember that he introduced the choral movement to Catalonia, as was beginning to happen in Northern Europe. He also provided cultural tools to the working class while promoting social associations beyond the strictly musical realm. His example was later followed by many similar organizations throughout Catalonia and the rest of Spain. Some of these would eventually include professional singers. The most influential of all—still active today—was the Orfeó Català, founded by the same promoters of the Palau de la Música Catalana: composers Amadeu Vives and Lluís Millet, the latter a close friend of Gaudí.

Catalan Folk Song

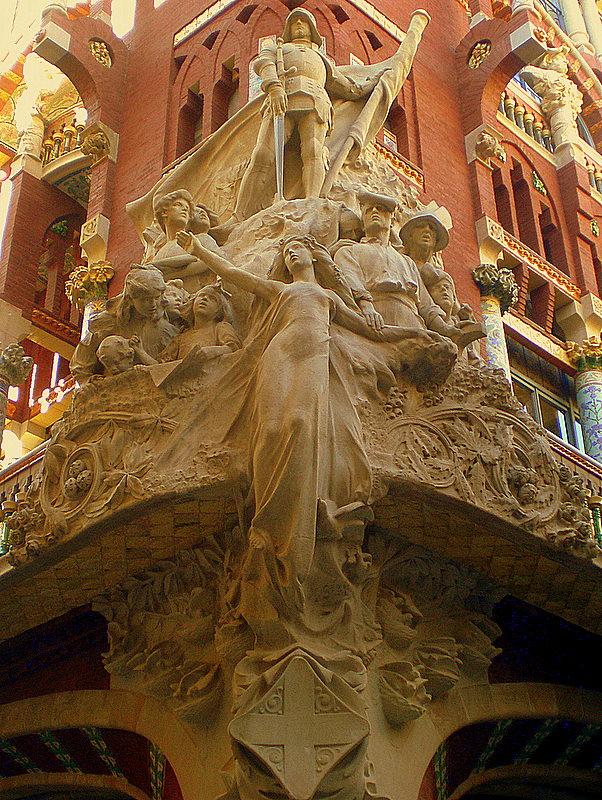

So far, we’ve seen the two sculptural groups inside the Palau de la Música Catalana. The third is located outside, on a corner of the building’s façade, like the prow of a ship. It’s called The Popular Song. Although sculpted by Miquel Blay, the iconographic program was designed by Domènech i Montaner himself, the building’s architect. The sculpture shows a maiden representing song, accompanied by the Catalan people, portrayed as characters of various ages and professions. “Above the group,” in Domènech i Montaner’s own words, “Saint George, patron of Catalonia, rises in a protective stance.”

It’s no surprise that this was the era when emblematic Catalan songs began to emerge, such as Els Segadors (1892) by Francesc Alió; L’Emigrant (1894) by Amadeu Vives, with lyrics by Jacint Verdaguer, the most admired poet of his time; or La Santa Espina (1908) by Enric Morera, with lyrics by Àngel Guimerà, another major literary figure of the moment. At the same time, there was a tireless search for old songs and traditions. One result was the revival of the sardana, which during this period became a national symbol.

It’s also no coincidence that during this time, various modernist musicians and artists promoted the Teatre Líric Català, a name encompassing a series of productions aimed at countering the dominance of Spanish-language zarzuela in Barcelona’s daily life (2). Among its main promoters were the aforementioned Enric Morera, author of the modernist masterpiece La Fada, and painter and theater entrepreneur Lluís Graner. While building Torre Bellesguard, Gaudí collaborated with Graner to decorate the Sala Mercè, a venue intended to serve as an example of a “total art space.”

It’s also no coincidence that modernism was the era of the first internationally renowned Catalan artists, such as Isaac Albéniz, Enric Granados, and Pau Casals—famous for harmonizing and internationalizing both Spanish and Catalan music, with a musical legacy that continues to be heard today.

Notes

(1) Aviñoa, Xosé (1985), La música i el modernisme, Ed. Curial, Barcelona, pp. 360–362.

See also: Harrison, Charles (2000), “What is Modernism?”, in Modernism, Tate Gallery Publishing, pp. 6–15.

(2) As an example, zarzuela was the most popular form of entertainment in 1898. However, at the time, works could be labeled differently depending on the source—such as “operetta” or “juguete”—which complicates any attempt at summarization. See: Lahera Aineto, Celestino (2013), “La recepción de la Zarzuela en la Barcelona de 1898,” Revista Catalana de Musicología, no. V, pp. 113–133.

(3) Alier, Roger (2004), “La música en el modernisme,” Enciclopèdia Catalana website.

(4) Vall i Comaposada, Josep M. (2014), Bellesguard. De la residencia de Martí el Humano a la torre Gaudí, Duxelem Editorial, pp. 122–123.

(5) Aviñoa, Xosé (1985), pp. 357–358. “The modernists turned their backs on Spain, not only due to a rejection of strict political centralism, but also—and above all—because they believed that true regeneration came from the north.” Nevertheless, some Catalan composers of the time were inspired by Spanish music, such as Amadeu Vives, Granados, or Albéniz.

(6) Ibid., pp. 339–343.

(7) The main reference work on today’s topic is the aforementioned book by Xosé Aviñoa (1985). In this book, the only chapter dedicated to a specific individual is that of Antoni Nicolau. Op. cit., pp.

(8) Gómez Amat, Carlos (2004), “Lírica y canción. Música coral,” in: Historia de la música española, vol. 5. Siglo XIX, Alianza Editorial, Madrid, pp. 100–101.

See also online: Puig Ortiz, Xaver, “Brief —Didactic and Informal— History of Choral Singing in Catalonia,” Palau de la Música Catalana website.