June 12, 2025

By Ferran Garcés

To conclude our series on music during the Modernist era, we’ll mention one of the lesser-known aspects of that time—an aspect present at Gaudí’s funeral, held almost exactly one hundred years ago today…

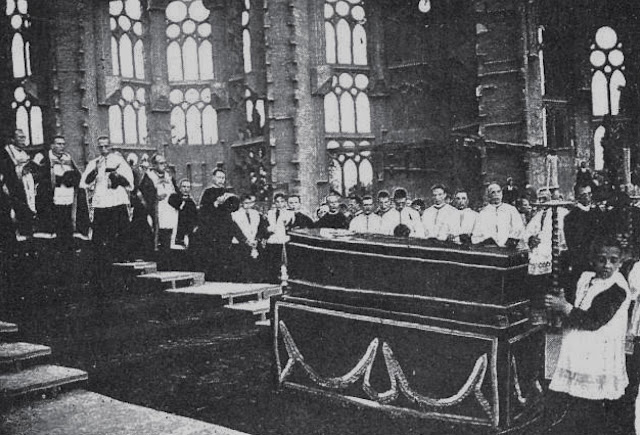

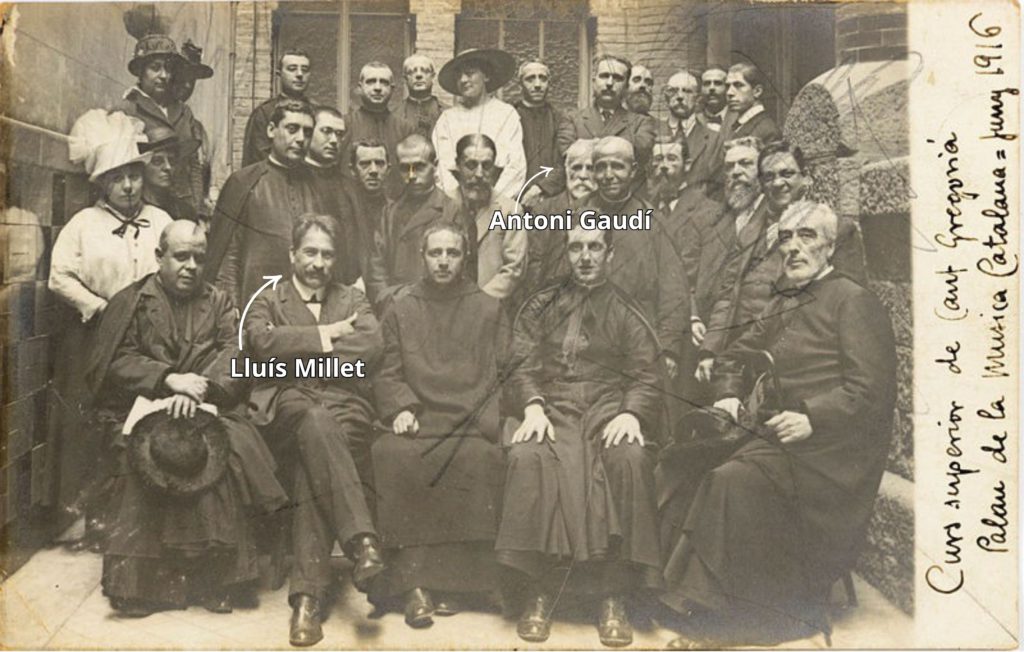

Let’s recall the events. On Monday, June 7, 1926, the architect was run over by a tram. At first, he was mistaken for a beggar. He died on Thursday the 10th. His burial, on Saturday the 12th, was worthy of a king. The final ceremony took place, as expected, at the Sagrada Família, where he would be laid to rest. The funeral music was performed by members of the Orfeó Català, led by its director, Lluís Millet, one of the leading figures in music during the Modernist period. This is the image shown at the top of the article. The chosen piece was the Requiem by Tomás Luis de Victoria, one of the foremost representatives of Spanish Renaissance polyphony. As we’ll soon see, this was no random choice…

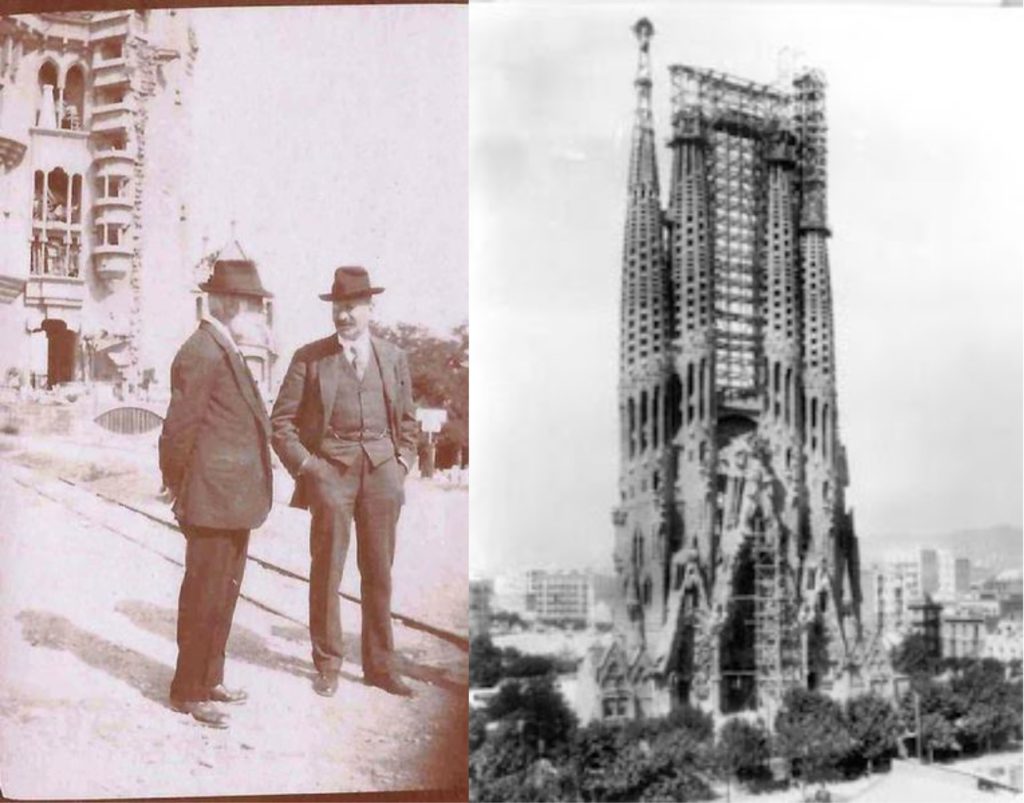

A close friend of Gaudí, Millet had carried one of the coffin ribbons throughout the funeral procession, which began at the Hospital de la Santa Creu, where the architect had been treated. For years, the two friends had often walked together. In fact, there’s a photo of them strolling beside the Sagrada Família, a temple that was just beginning to rise at the time (for interested readers, note the existence of the “Lluís Millet i Pagès Collection” at the Orfeó Català Documentation Center, full of images from that era: CDOC).

Now, with the preamble complete, we can delve into today’s topic. The two friends shared, above all, a deep passion for Gregorian chant, medieval sacred music, and Renaissance polyphony—two styles rarely associated with Catalan Modernism, yet highly regarded at the time, even if the topic remains under-researched and little known (1).

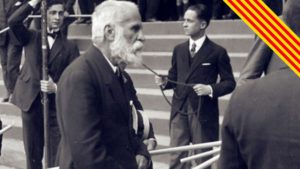

In the following photo, we see Gaudí and Millet among the participants of the first Gregorian chant course at the Palau de la Música Catalana, held in 1916. It was taught by Gregori Maria Sunyol, a monk from Montserrat who came to Barcelona specifically for this purpose.

A Return to Musical Origins

A Return to Musical Origins

Gregorian and polyphonic chant during the Modernist era echoes the architect’s most famous quote: “Originality consists in returning to the origin; thus, original is that which returns to the simplicity of the first solutions.” This is precisely what happened as Gaudí built the Sagrada Família…

Throughout the 19th century, religious music had become overly sophisticated, increasingly featuring professional singers and instruments typical of secular music. By the end of the century, a group of monks launched the Cecilian movement (named after Saint Cecilia, the Catholic patron saint of music). Their goal was to restore the simplicity of original Catholic liturgical music—namely, Gregorian chant and select Renaissance polyphonic works, such as those by Tomás Luis de Victoria.

Finally, on November 22, Saint Cecilia’s Day, in 1903—the same year Gaudí completed the Torre Bellesguard—Pope Pius X issued the Motu Proprio Tra le sollecitudini, an influential decree that laid the foundation for a return to the purity of early Christian music (2).

In Catalonia, the cause found many supporters, although, as mentioned, it remains underexplored and underpublicized. Tomás Luis de Victoria, long neglected, was revived by Felip Pedrell, the leading musicologist of Gaudí’s time. Publishing all his works took years, from 1898 to 1913. Gaudí’s contemporaries were thrilled to hear his music again. Another promoter of the music endorsed by Pius X was Lluís Millet, a close friend of both Gaudí and Pedrell (4).

Millet is famous for founding the Orfeó Català and the Palau de la Música Catalana, as we saw in our previous article (link). What’s less known is that Millet, like Gaudí, was a devout believer and a leader in implementing the Vatican’s liturgical reform. Millet was also a member of the Diocesan Commission for Sacred Music in Barcelona and the chapel director of a church that Gaudí was heading to on the day he was struck—Monday, June 7…

Gaudí’s Favorite Church

Yes, indeed, we’re talking about the Church of Sant Felip Neri, the architect’s favorite place to hear—and sing—Mass. In fact, this church houses a rather exceptional painting (link). It was painted by Joan Llimona, one of the great Modernist artists and, like Gaudí, a regular parishioner at Sant Felip Neri. Despite the architect’s famous shyness, Gaudí agreed to model for the face of the Italian saint out of friendship. In the painting, we see the architect on a mountain, surrounded by boys singing and playing instruments. The image recalls the origin of the oratorio musical genre, born within the Congregation of the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri, also known as the Oratorians.

This makes it easier to understand why, that June day in 1926, Gaudí was heading to Sant Felip Neri—a deeply rooted habit. Gaudí didn’t just go to “listen” to music; he went to “sing” it. Another participant in the Gregorian chant course mentioned earlier was Francesc Pujol, a composer and musicologist who served as assistant chapel master at the Church of Sant Felip Neri.

The Music of Heaven

Gaudí opposed Masses sung by professional choirs and soloists, which turned attendees into mere spectators. He said: “The people sing—if not the patriotic hymn, then the revolutionary one; if not the religious song, then the blasphemous and obscene one. It is therefore necessary that the people take part in the Church’s songs” (5). He also stated: “The Gospel and Saint Paul both say that the sense of hearing is the sense of Faith” (6).

On another June day, the 29th of 1922, Antoni Gaudí visited the Orfeó Català in Barcelona. There, he was asked to sign the institution’s guest book (7). The architect, also a skilled draftsman, improvised an allegory of Orpheus, the mythical Greek hero, playing the harp and surrounded by animals. Beneath the illustration, he wrote the following dedication: “In Heaven, we will all be Orfeonists.”

Notes

Notes

(1) Aviñoa, Xosé (1999), History of Catalan, Valencian, and Balearic Music, IV. From Modernism to the Civil War (1900–1939), Edicions 62, Barcelona, pp. 189–210.

(2) The full text can be consulted at: Del Toro, Raúl (22/11/2014), “Saint Pius X and Liturgical Music. 2 – The Motu Proprio Tra le sollecitudini”, Info Católica website.

(3) Gustems-Carnicer, J., Calderón-Garrido, D., Arús-Leita, E. (2018), “The Invisible Breath: Music and Sound in Gaudí’s Work”, Barcelona, Research, Art, Creation, 6 (1), pp. 72–89.

(4) Millet and Pedrell

(5) Bergós i Massó, Joan (2011 edition), Gaudí. The Man and the Work, Lunwerg, Barcelona, p. 44.

(6) Puig-Boada, Isidre (1981), The Thought of Gaudí. Compilation of Texts and Commentary, Col·legi d’Arquitectes de Catalunya, Barcelona, p. 226.

(7) Grassot, Marta (05/02/2021), “The Golden Book of the Orfeó Català”, CEDOC website.