By: Ferran Garcés

Last week was Sant Jordi. A celebration that, among other attractions, represents a true celebration of dragons, the most popular fantastical beast worldwide. To commemorate it, they began a series of articles about the peculiar evolution of the forms – and the meaning – of dragons. An evolution we can illustrate with the four dragons of Torre Bellesguard.

In the first installment, we talked about the original dragon, in the form of a serpent, and the medieval dragon, which, in addition to adding wings and legs to its appearance, becomes synonymous with the Devil. A terrible monster, enemy of saints and holy figures, as a recreation of the eternal struggle between Good and Evil. However, despite such bad press, the dragon has become a very popular animal. How has this been possible? To answer this question, we must remember, above all, that dragons have not always been a diabolical figure. We will get to know the less evil dragons…

The “standard” dragon

Carlos Alvar, a renowned Spanish medievalist, distinguishes between the “medieval ecclesiastical dragon”, associated with the demonic dragon, antagonist of saints, and the “lay dragon”, typical of Arthurian legends, which “did not represent so much the image of Evil linked to the Devil, but rather the just adversary of the hero” (1). This dragon, a symbol of strength and power, became the standard of different knights, military orders, and even kings, and by extension, their kingdoms. Not long ago, “Uterpendragó”, the father of the famous Arthur of Camelot, already used the dragon as a distinctive emblem, and before him, the Romans and the Vikings (2).

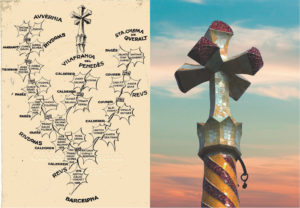

In the Crown of Aragon, the first monarch to adopt the symbol of the dragon was Peter IV, the father of Martin I the Human, the king who resided in the original castle of Bellesguard, between 1409 and 1410. From this latter monarch, a well-known heraldic figure is preserved: the representation of a winged dragon on his helmet. Since 1407, by a concession from Martin I, it has been part of the Feast of the Standard, the main festivity of Mallorca, although, this year, it is a subject of controversy due to requests for the original crest, now in Madrid, to return to the Balearic island (3).

Another controversy surrounding this peculiar winged dragon, known as a viper, is that which revolves around its appearance because, over time, it has varied considerably in shape, oscillating between the scorpion, the bat, and a female dragon. Be that as it may, the viper often accompanies the king’s crest or the four bars of the Royal Seal. A symbol that has endured in the coat of arms of Valencia and, until recently, in that of Barcelona (4). It is also the case with the viper of Torre Bellesguard, with the flag of Catalonia in the form of a shield under its wings.

Today, both the traditional dragon and the viper are part of the festive bestiary, a set of figures made of painted cardboard that appear on the streets on holidays like Corpus Christi. When we delve into the origin of these processions, we find again the name of King Martin I because, in the coronation ceremonies of this monarch, held in Zaragoza on April 13, 1399, he and his Barcelona advisors were accompanied by two of the first figures of institutional festive imagery in Barcelona: the Eagle and the Viper, emblems that had already been used two years earlier in the celebrations of the entry of the same monarch into the city (5). By the way, the first time the viper, distinguished from the dragon, is documented is in the description of this celebration (6).

On the other hand, in 1408, the year Martin I began to build Bellesguard, the Order of the Dragon was founded, to which Oswald von Wolkenstein, a famous German poet, belonged, who, in one of his poems, speaks of Margaret of Prades, the queen whom Martin I married at Bellesguard (7). We see, therefore, how different personalities of the time adopted the distinctive emblem of the dragon, an unusual association if the animal were only an incarnation of the demon, and we also see how the time of the ancient castle of Bellesguard was an influential chapter in the history of dragons, parallel to the legend of Saint George. In summary, the dragon could be a terrible enemy but also a powerful talisman. The following dragons bear witness to this latter characteristic.

The Water Dragon

In ancient myths, the main function of dragons was to protect waters, caves, and other remote places for humans, usually with a hidden treasure. Dragons that poets often describe with great wisdom and sometimes even the gift of prophecy.

This is the case of the third dragon of Torre Bellesguard, although, today, it is not part of the visit because it is on the private land of some neighbors. It was built to shape the house of a well with a depth of 40 meters and through which an underground stream still flows (8). This fact, on the other hand, reminds us how water is the secret protagonist of Bellesguard, both because of this stream, or mine, and the presence of a torrent in the place where now runs the Bellesguard street.

The Guardian Dragon

While the well dragon connects Bellesguard with the subterranean or chthonic world, the fourth dragon of the Tower sticks its head out to the roof, protecting the horizon line (9). Its discovery represents the most fascinating point of the visit. With its two enormous eyes, it is the dragon that best describes the origin of the name of such a fabulous animal. Indeed, the word dragon comes from δέρκομαι (“deɾkomai”), a Greek verb meaning “to stare”. The ancient Greeks used it to name snakes, δράκων (“drakon”), convinced that this animal, since it has no eyelids, can keep its eyes always open and become, consequently, an extraordinary guardian (10).

And what is curious. The word guardian comes from a Germanic verb, wardon, which also means the same as δέρκομαι, that is, “to stare, watch, guard, protect” (11). Bellesguard, in fact, is a play on words that means both “beautiful views” and “good shelter”. It was King Martin himself who chose it, perhaps advised by Bernat Metge, his main advisor and great writer. As soon as the visitor climbs to the terrace of the current building built by Gaudí, the denomination of the place is understood, due to the spectacular views that allow us to enjoy – and dominate – the entire landscape of the plain of Barcelona. With four dragons, and one of them, the largest, perched on the same roof, it is surely a well-guarded place…

Notes

(1) Alvar, Carlos (2004) Espasa Dictionary of Arthurian Legends, Espasa, pp. 136-137.

(2) The standard of the Romans was called “signum draconis”, or “draco”, and its bearer was called “draconarius”.

The Viking ship known as a drakkar often receives this name because, frequently, the figurehead was carved in the shape of a dragon.

(3) Pol, Antoni (12/7/2019), “A 90-year struggle: Palma claims King Martí’s crest”,

(4) García, Edu, “The coat of arms of Barcelona, the crest of the viper, and King Jaume’s ratapinyada”, Barcelona is powerful blog.

(5) Hughes, Robert (1992), Barcelona, Anagrama, Barcelona, p. 211-212.

Vilarrúbias, Daniel (2017), “The fire of the entourage. Festive devils and Fire Bestiary, from origins to 1936”, Barcelona City Council.

The fire of the entourage. Festive devils and Fire Bestiary, from origins to 1936

(6) Anonymous, “Corpus 700 Drac”, Bestiary website, Festive and Popular Bestiary Group of Catalonia. At the end of this article, interested readers will find an extensive online bibliography on the topic.

At the end of the following article, the first mentions of the viper are mentioned chronologically during the reign of King Martí and after him: Ollé, Manel (1992) “The viper. Four notes about the life and customs of this unique creature”, Government of Catalonia and Barcelona City Council (Sant Martí District)

(7) Bonet, Miquel (2018), “In times of Queen Margarita de Prades”, Catalunyadiari

(8) In this book, you can learn a little more about the well-dragon: Valls, Mireia (2012), The Underground Barcelona, Mediterrània Publishing, Barcelona, p. 101-103

(9) It should be clarified that, for a long time, this dragon remained unknown even to the owners. Its discovery was made in 2009 by Jan Molema, a well-known specialist in Gaudí’s work. More information: Molema, Jan (2009), Gaudí. The Construction of Dreams, Thieme MediaCenter, Rotterdam, p. 250

(10) Álvarez, Javier: “Etymology of dragon and its relation to snakes”, “Grammatical history of Spanish” blog

(11) Soca, Ricardo: “Etymology of the word: guard”.