By: Ferran Garcés

We have started the year talking about the animal symbols of Bellesguard. We have also mentioned that the tower was built in two phases. The first, from 1900 to 1909, is led by Gaudí. The second, around 1916, corresponds to Domènec Sugrañes, one of his closest collaborators (he would continue the Sagrada Familia after the master’s death). The animal motifs of Bellesguard were added in the second phase, and we do not know if they follow Gaudí’s original plan or are an idea of Sugrañes himself. In any case, they have been part of the house since the time of its first owners, the Figueras family.

Today’s animal, the last on the list, is the least visible and, at the same time, the most challenging to document regarding its authorship. We find it in a pig in a garden area called “Andalusian patio.” At the base of the pig, we see a motif that repeats in the tower’s vestibule, decorated tiles with roosters and lions. However, on the pig’s belly, we discover a motif found only here: the Phoenix, which, along with the spiral, are symbols of the Renaissance, the cultural, political, and artistic movement in which Torre Bellesguard is framed. But before that, let’s take a brief glimpse into the history of this captivating symbol…

Companion of the pyramids…

The Phoenix is a famous male bird known for its ability to rise from its own ashes. Its myth originated in the land of the pharaohs, where it was called “bennu” and took the form of a heron. The Egyptians associated it with the flooding of the Nile as well as the sun’s return each morning. The Greeks and Romans turned it into a symbol of eternal life, but in the form of an eagle with crimson-colored plumage, explaining the use of the word “phoinix” (Latin for purple or crimson). Later, Christianity adapted it to its unique belief in resurrection.

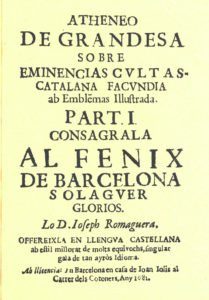

As this fabulous bird is the only one of its kind and never goes extinct, during the Baroque period, the term Phoenix became synonymous with a unique and excellent person or thing. For example, the Madrid playwright Lope de Vega, due to his prolific literary production, was called the “Phoenix of the ingenios” (geniuses). With the same meaning, we read the phrase “to the glorious Phoenix of Barcelona, Saint Oleguer” on the cover of the Atheneo de Grandesa, an emblem book written by the erudite Barcelonian Josep Romaguera.

The dedication’s Oleguer refers to an archbishop and saint of the city, as Romaguera’s work, written in Barcelona in 1681, was printed under the censorship of the Holy Office, necessitating ecclesiastical approval. The most relevant part of this book is the prologue, as it constitutes one of the earliest defenses of Catalan as a literary language in a time dominated by the use of Spanish. Indeed, Romaguera was one of the few Baroque poets who wrote in Catalan, as well as a prominent member of the Academy of the Distrustful, an institution that, around 1703, had its headquarters in Bellesguard when it was owned by the poet and military man Joan de Gualbes i Copons. Like most of its members, during the War of Spanish Succession, they supported Archduke Charles. After the occupation of Barcelona in 1714, King Philip V closed the academy. Nevertheless, just like the Phoenix, the impetus of Romguera and Gualbes would rise from their ashes in Gaudí’s time…

Companion of Palau Güell and Torre Bellesguard

In the late 19th century, the image of the Phoenix would become a symbol of the Renaissance, the movement aiming to revitalize the culture, politics, and economy of Catalonia. Gaudí and the first owners of the property, the Figueras, were active members of this movement, along with other artists and bourgeois of that time. The most famous example is the header of a newspaper called La Renaixença. It was precisely designed by the architect and friend of Gaudí, Lluís Domènech i Montaner, in 1880. In it, we see a Phoenix, with its classical iconography, the same as the pig in Bellesguard: a profile head and raised wings.

The spiral, the concealed Phoenix

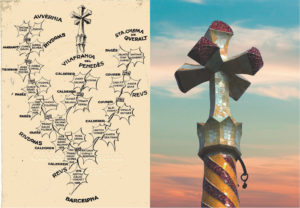

The promoter of the newspaper La Renaixença was Eusebi Güell, Gaudí’s great patron, and precisely, the other prominent Phoenix of this time is the one Gaudí designed for him at the palace named after him on Nou de la Rambla street. It welcomes pedestrians just at the entrance of the building, atop a medieval helm resting on the shield of Catalonia, with the four bars arranged helically. A geometric device that Gaudí would repeat, replacing the wrought iron of the Palau Güell sculpture with a trencadís of glass pieces on the pinnacle of Torre Bellesguard. This decorative motif serves as a reminder that the spiral, like the Phoenix, was another symbol of the Renaissance…

Let’s remember that the spiral is a curve that seems to have no end. Each turn suggests the Phoenix rising from its ashes. It is not surprising, therefore, that this geometric shape is so present in Gaudí’s work, both in decorative and structural aspects. However, at Torre Bellesguard, it is less visible on the outside because, in homage to the disappeared medieval castle of King Martí I l’Humà, Gaudí adopts the straight lines of neo-Gothic. Inside, though, the entire tower spirals up to the pinnacle, crowned by the helical flag of the rooftop. The spiral is also present in the small decorative details that adorn both the garden and the interior.