By: Ferran Garcés

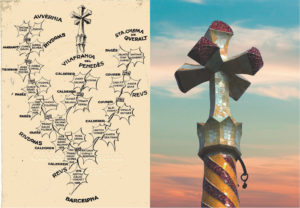

In a few days, it will be Saint George’s Day. A celebration that, among other attractions, represents a true celebration of dragons, the most popular mythical creature worldwide. On the other hand, the dragon is one of the local symbols most associated with the figure of Antoni Gaudí and Barcelona. A curious fact because, apparently, dragons are usually associated with Evil and even with the Devil himself. How then could such a wicked beast become so popular?

Fortunately, at Torre Bellesguard, we have four dragons, and each one allows us to illustrate the main stages of the evolution of an ancient creature, from malignant to benevolent. To get to know them, and thus answer the question, we will write two articles. Today, we will talk about the original dragons and the dragons associated with the Devil, but don’t worry, next Friday we will discover the protective dragon, closer to the festive character of this fantastic creature today.

The original dragon

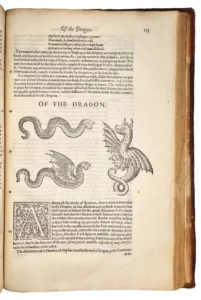

The word “dragon” comes from the Greek word δράκων, which will pass into Latin as “draco, -ōnis”. In both cases, the term refers to a serpent. For this reason, in Greco-Roman paintings and sculptures, heroes like Hercules, Cadmus, or Jason face dragons in the form of serpents. The constellation of the dragon (draco) is one of those serpents. In Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest religions, we find Zahhak, a three-headed dragon, whose name, in Avestan, means “Great serpent”. The Asian dragon, originally, is also a great serpent. However, over time, dragons, all over the world, have not stopped adopting new elements in their original appearance, such as wings, legs, horns, or teeth in the mouth. Edward Topsell, an English clergyman fond of bestiaries, published in 1607 a curious book titled The History of Four-Legged Beasts and Serpents. In the chapter dedicated to dragons, he summarizes very well the evolution of this fabulous beast.

Consequently, the renowned writer Jorge Luis Borges, in his Book of Imaginary Beings, the first thing he says is: “The dragon has the ability to assume many forms, but these are inscrutable”. In other words, the history of dragons is difficult to summarize. However, we will try, as we have said, based on the four dragons of Torre Bellesguard.

The dragon that is not a dragon…

First of all, it must be clarified that not everything that looks like a dragon is a dragon. For example, the griffin, has the head and legs of a bird of prey, like an eagle. In other words, it is not a serpent. Another figure that is confused with dragons are the heraldic lions, like the ones we see in the vestibule of Torre Bellesguard, and which, once again, are not dragons because they lack the original serpentine aspect.

The malignant dragon

By the end of the Middle Ages, the enemies of dragons are no longer heroes but saints, or even the Mother of God herself, who is sometimes represented trampling on a serpent. The most famous of them all is Saint George, but there are others, such as Saint Michael, or Saint Martha of Bethany. In these hagiographic legends, the dragon becomes synonymous with the Devil under the influence of the Book of Revelation, where an “ancient serpent” attacks a woman identified with the Mother of God.

Around 1260, another book will influence even more the popular imagination. The Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine. It is a collection of stories of saints, which enjoyed enormous success. Behind the Bible, it was the most read and copied work. Its miniatures will be the reference for all subsequent paintings and reliefs of the legend of Saint George, or of the aforementioned Saint Martha of Bethany.

However, while the figure of the saint, or of the saint, soon unifies with its own iconography, the representation of the dragon will never be the same, as if every artist wanted to compete in creativity with their predecessors when giving shape to the terrible beast. It will be like this that the original serpent will acquire “the ability to assume many forms”, and all of them will become “inscrutable”, as Jorge Luis Borges commented.

At Torre Bellesguard, we can see a recreation of the legend of Saint George and the dragon, in the main scene of the wrought iron hanger in the house’s vestibule. In it, we recognize the traditional iconography that has served as the basis for the celebration of Saint George. Next Friday we will see the other dragons of Torre Bellesguard. Today, to finish, we want to wish you a happy Saint George’s Day and remind you that our dragons await you eagerly to celebrate such a captivating day, and the rest of the year. They will not move from here. They are waiting for you…

Notes

(1) Martínez, Josep (2019) Drakcelona, Arola, Barcelona.

(2) Today, only three can be seen, because the fourth dragon is on private land belonging to a neighbor. On the other hand, Torre Bellesguard not only hides dragons but also other imaginary creatures.

Garcés, Ferran (1/02/2024), “The Bestiary of Bellesguard III: Dragons and other fantastic beasts”, Bellesguard blog.

(3) Borges, Jorge Luis: The Book of Imaginary Beings, EMECE Editores, Barcelona, 1990, pages 78-86

(4) Gonzalez, Teresa, and Alert, Fina (2011) The Hidden Bestiary of the MNAC. Romanesque Art, MNAC, Barcelona, p. 31-34 (“dragon”) and p. 35 (“apocalyptic dragon”)

The main saintly dragon fighters, in addition to Saint George and Saint Michael, are: Saint Bernard, Saint Margaret of Antioch, Saint Martha of Bethany, and Saint Sylvester.

(5) The dragon of Saint Martha is called “tarasca”, or “Cuca Fera”, and this year is one of the main pieces of the processional imagery of Barcelona.